Balance Sheet Breakdown

This post aims to get you comfortable with what a balance sheet is, and the main categories. Once we have a solid understanding of the key items, we will explore how to use the information on the balance sheet to provide insights.

I will split my explanation of a balance sheet into three levels. Through this storied approach, you can revisit a part if feel lost and/or uncertain.

- Level 1 is a basic description of balance sheet categories.

- Level 2 lays out the five main categories of a balance sheet.

- Level 3 will further break down the main categories with pictures

Level 1 Breakdown

A balance sheet is a high-level summary of a company’s possessions at a point in time.

There are two sides to a balance sheet: 1) Assets, and 2) Liabilities and Shareholder Equity

Assets: What the company owns

Assets are what the company uses to generate profit such as property, factories, equipment, inventory etc. The value of these assets is recorded to show a high-level summary of what the company owns.

Liabilities & Shareholder Equity: How the company funded their assets

Liabilities are money the company owes or, in certain cases, commitments to provide services that have been paid for upfront but have not been completed yet. An example of the former is debt – a company owes money to a bank. An example of the latter is a software company receiving an upfront payment on January 1st for a year’s subscription, with the commitment to provide the software throughout the year.

Shareholder Equity represents the amount of money shareholders would collect after selling all their assets and paying out all the money it owes (its liabilities). It is also equal to the initial investment made into the business plus any profit retained in the business.

Level 2 Breakdown

Assets: What the company uses to generate profit.

Assets are broken down into two categories: A) Current Assets, and B) Non-Current Assets.

Current Assets

Current Assets are items used in the day-to-day activities of a company’s operations to make a profit. The main categories of Current Assets are Cash, Inventory, Accounts Receivable, and Pre-Paid Expenses. We call these assets “current” because they “convert to cash” within 12 months – i.e., changing from their current form into cash within 12 months (see Level 3 for explanation).

Key Takeaway: These assets are core to the daily exchange of goods & services.

Non-Current Assets

Non-Current Assets are assets that enable day-to–day operations to occur. These assets last longer than 12 months and enable continuous operations. The most common example of this is Property, Plant, and Equipment (“PP&E”). For Charlie, his stores – Property – enable sales to take place with customers. The large industrial ovens – Plant and Equipment – bake his biscuits from the batter every day.

Key Takeaway: Long-life assets are used to produce/offer, a good and/or services.

Liabilities: Money owed to someone, or commitment to provide a service with cash already received.

Current Liabilities

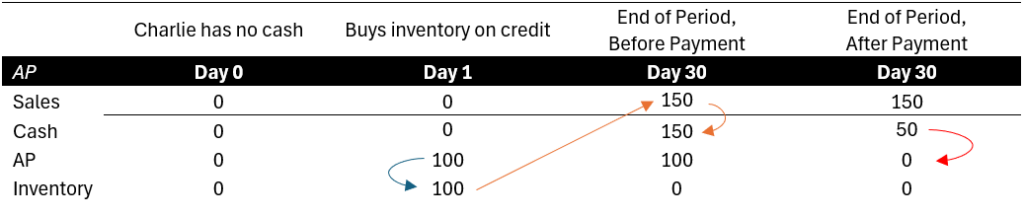

Current liabilities are cash owed that needs to be paid within 12 months or less. The main categories are Accounts Payable, Accrued Salaries & Wages, and Short-Term Debt (the portion of debt that must be paid back within 12 months). Current liabilities allow a company to pay suppliers, vendors and employees on a delay. The mechanism temporarily delays “cashflow outflows” (expenses) allowing the company to generate “cash inflows” (sales) to pay back suppliers.

E.g., Employees are often paid every two weeks versus daily. Meanwhile, during the two weeks, a company will generate sales and receive payment from customers – cash. The company will also have “accrued salary expenses” creating a liability – cash owed to employees. Thus, the company can pay its staff at the end of the two weeks with the cash generated during the period.

Key Takeaway: Non-current liabilities lubricate the cash flow dynamics of a company. This allows companies to first, generate cash inflows (sales), and pay outflows (expense) at a slight delay once cash is received. (We will see this is a slight simplification but is good for now).

Non-Current Liabilities

Non-current liabilities are money that needs to be paid any time beyond 12 months. This category is largely debt that comes due anytime after the next 12 months.

Key Takeaway: Money the company uses instead of the owner injecting more cash.

Shareholder Equity

The total investment made into the business by the owners plus any profit retained in the business. We won’t go deeper than this for now because this is the key point.

Key Takeaway: How much money an owner has invested into the business as well as the profit kept within the business.

Expert Point

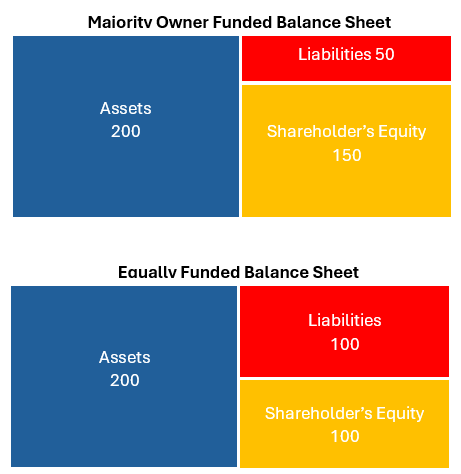

Liabilities are not bad unless a company cannot pay them off when they come due. In fact, when used responsibly, liabilities help business owners generate the same while using less of their own money. Wait a second… Doesn’t this sound familiar?

If we think back to ROI, we can see how liabilities can be advantageous. If an owner increases the business’s liabilities, instead of investing more of their money, they use someone else’s cash to fund their balance sheet. Since the balance sheet is how operations are funded, they are using other peoples capital to generate profit. As an owner, your ROI or Return on Equity (explained in the next post) increases. However, there is more risk. If you default on your loan, you can lose your business. I have seen many businesses use this to their advantage, while others take on too many liabilities eventually going bankrupt – more on this to come. Think about this snippet here – it is powerful.

Level 3 Breakdown

Let’s use an example and some sketches to illustrate these concepts. Our favourite entrepreneur is still selling his so scrumptious Cinnamon Charlies.

Current Assets

Cash

The value of a company’s cash and financial assets that can be converted into cash immediately (e.g. government debt).

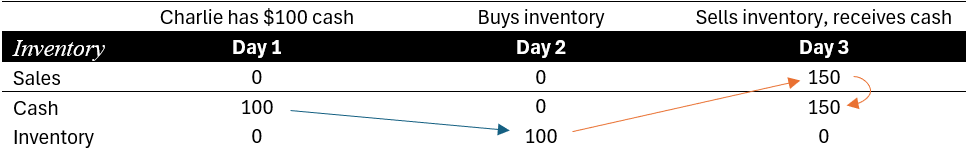

Inventory – A) Raw materials, B) work-in-progress, and C) finished goods

Early in the morning, Charlie buys $100 of raw materials (flour, eggs, sugar, cinnamon). From the moment he acquires the raw materials to the finished product, the $100 he spent is considered Inventory. A customer now enters the store and purchases all Charlie’s biscuits, paying $150 for the biscuits with cash ($50 profit). You can see how inventory “converts to cash” in the table. If inventory doesn’t convert to cash within 12 months there is likely a problem e.g. inventory has expired.

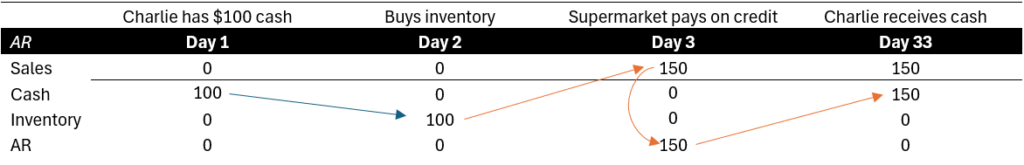

Accounts Receivable - Money owed by customers for goods/services invoiced or delivered but not paid.

Using Charlie as an example again, imagine he has sold his $100 of inventory and delivered it to a supermarket for $150. The supermarket promises to pay him in 30 days. The $100 of inventory, will turns into $150 of accounts receivable. When Charlie receives the $150 from the Supermarket his Accounts Receivables balance turns into $150 of cash i.e. AR converts to cash.

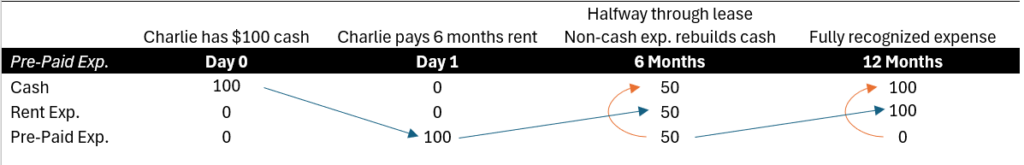

Pre-Paid Expenses – an expense paid in advance and used within 12 months.

Charlie pays a year of rent upfront for his store. Since Charlie will occupy the store for 12 months, and his lease hasn’t even started, he creates a “pre-paid expense” account to show future benefits he is entitled to. Over the lease, the balance will get expensed equally the leases to show the “underlying” monthly rent expense on the P&L. However, the monthly expense recognized will be “non-cash” so cash outflows will be lower than stated expenses creating a cash inflow effect and therefore rebuilding the cash balance.

Non-Current Assets

Property, Plant & Equipment

These are assets that enable day-to–day operations typically involved in the creation of goods and services or buildings that house the exchange of goods and services.

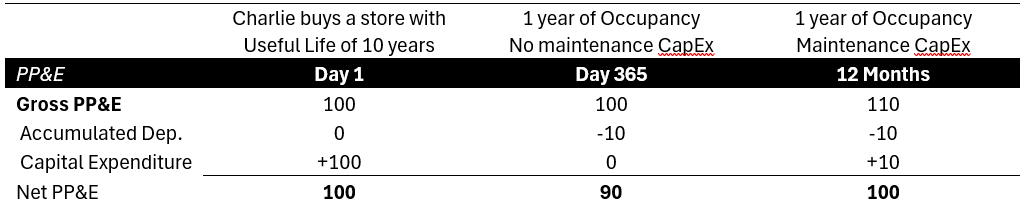

PP&E is measured using the actual purchase cost, or “historical cost”. For example, Charlie purchases land, a building, and equipment for a new store. The historical cost could include the purchase price, transaction fees, and any improvements made to the building. Importantly, one must pay for all PP&E upfront. Since we can use PP&E for a long time, we “capitalize” the investment (add the total investment value) on the balance sheet. Adding this all together is called the “Gross PP&E” value.

If we do no maintenance work, the building and equipment will eventually break down from consistent usage – asset deprecation. To represent the economic wear and tear of buildings and equipment accountants use depreciation expense. To determine the depreciation expense, we need to estimate the rate at which an asset breaks down (depreciates) – its “useful life”.

Say a building for a store costs $100 (I know… cheap real estate!), and we are confident the building will be functional for 10 years. We would allocate the $100 over its useful life of 10 years. That means a depreciation expense of $10 a year to account for the decline in value.

The gross value of PP&E is adjusted for total accumulated depreciation to arrive at Net PP&E. Next year, the Net PP&E value would be $90 if we didn’t spend money to repair the depreciation ($100-$10 = $90). Total depreciation expense over the lifetime of PP&E is called accumulated depreciation.

Notice the difference in the timing of cash flows vs the expenses recognized. PP&E is purchased upfront. The depreciation expense is recognized over the asset’s lifetime. At the end of the asset’s life, the gross (total) depreciation expense will equal the initial purchase price. Accounting delays the total expense to match the useful life of the corresponding PP&E asset. Business accounting thus “smooths” the large cash outflow from the initial purchase into later years. It is as if we could purchase X% of the asset every year – in Charlie’s case 10% of the store. Importantly, however, notice that depreciation expenses are non-cash. Charlie already paid for the store a prior period. Thus depreciation expense is just a representation of the expense in business accounting but does not represent a cash outflow.

Moreover, a company can expend money on PP&E for two reasons: A) To grow PP&E to add capacity or B) to maintain/service existing PP&E and offset the “depreciation”. This is called Capital Expenditure (“CapEx”). The value of total CapEx is added to “Gross PP&E”.

Land assets are not depreciated because of their potential to appreciate and are always represented at their current market value.

Current Liabilites

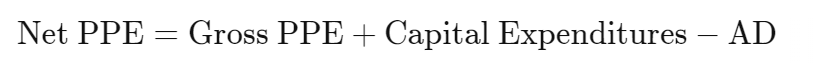

Accounts Payable - Money owed to suppliers if they have received goods but haven’t paid for them.

Charlie has ordered $100 of sugar, eggs, flours and his secret ingredient (which we cannot name) adding to inventory. But Charlie will only generate the cash needed to pay his suppliers once he sells his biscuits to customers and receives payment. So, Charlie uses credit to pay his suppliers supplier, thereby increasing the money his business owes (Accounts Payable) but conserving cash. Once Charlie sells his inventory and receives cash, he can pay back suppliers and decrease his accounts payable balance.

Accrued Salaries - money owed to employees for work not yet paid.

Charlie pays his employees every two weeks. During each two-week period, however, Charlie will try to generate cash inflows (sales) to cover his expenses and make a profit. At the end of the two weeks, his company will also have “accrued salary expenses” (expenses recognized on the P&L but have not yet been paid) creating a liability owed to employees. He can pay his staff at the end of the two weeks with the cash generated during the period.

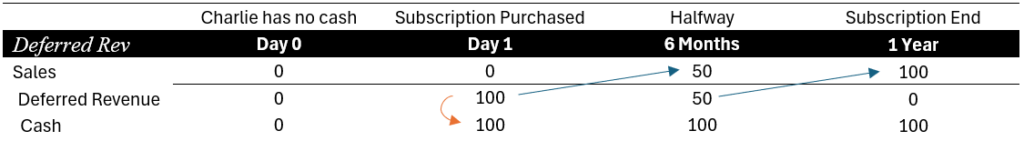

Deferred Revenue – A service that the company has been paid upfront but has not completed the service.

Imagine Charlie has a small software business. A customer must pay Charlie when they subscribe – cash up front. He notes down a liability of corresponding size – deferred revenue – to show the obligation his customer. The Deferred revenue converts to actual “revenue” as Charlie fulfils the obligation over time.

Deferred revenue is interesting – one receives cash a year early vs paying money owed 2 weeks later. The upfront cash is called “float”. When Charlie receives the float, he gets all revenue (thus profit) before it is “earned”.

Float is a technical idea which we will further explain in another piece. However, very basically, if one can receive upfront all the cash needed to pay our expenses for the next year and have leftover profit, one can see how advantageous this can be. If we invest the float at a profit, it can be used to make investment profit, in addition to normal operating. The added profit will increase our ROI by a percentage point or two without a business model change. Over time, the added percentage points to the ROI will have a huge impact. Don’t worry about the math now. We will break float down at a later date. I want you to just recognize that it is very advantageous to get your revenue paid upfront!

Non-Current Liabilities

Debt

Debt reasonably easy to conceptualize. Debt increases your cash, but also your liabilities as you need to pay back the loan at a particular date with interest according to the agreement. I won’t go into detail here.

Shareholder's Equity

Refer back to prior levels.

Concluding Thoughts

Balance sheets are scary. Now, you have a better handle on what the major items are. Increased understanding will give an important knowledge base that we can use to deduce information. So now what?

The next steps are to take the information on a balance sheet, use some ratios and see what is happening in our business. All to come in the next piece – see you there!